In the heart of Srinagar’s old city, Bandook Khar Mohalla, a locality in Rainawari known for its skilled gunsmiths, now stands as a testament to a fading craft. Surrounded by the historic Malkha graveyard and heritage buildings from the Maharaja’s era, this area owes its name to its long association with gun-making. Once a vibrant hub of artisans catering to a vast clientele, the gunsmithing trade is now on the brink of extinction, with craftsmen desperately fighting for its survival.

Historical Legacy of Gun-Making

The craft of gun-making in Kashmir traces its origins to the Dogra rule during the mid-19th century. In 1848, Maharaja Gulab Singh recognized the mechanical skills of the residents of Bandook Khar Mohalla, describing them as “engineers by profession.” British gunsmiths trained the locals under the Maharaja’s guidance. By 1944, Maharaja Hari Singh introduced a formal system for gun ownership and documentation.

In 1962, the Government of India mandated that all guns manufactured in Jammu and Kashmir be tested at Ishapore, West Bengal, to meet official parameters. This regulation forced many local factories to close. Of the 15 gun factories in the area, only two survived: the Subhana Gun Factory (established in 1925) and the Zaroo Gun Factory (established in 1940).

Nasir Ahmad, one of the owners of Subhana Gun Factory, recounts: ”In 1962, we had to send six guns for testing but initially forgot to include the documents. The guns didn’t meet the government’s parameters, but the factory stood strong despite the setback.”

Decline of a Craft

The Wildlife Protection Act of 1978 dealt the first major blow to the industry, banning hunting and significantly reducing the demand for guns. The situation worsened during the political unrest in 1989, when gun factories were temporarily shut down, leaving owners and workers in dire straits.

In 2016, the Arms Act imposed stricter guidelines, making it nearly impossible to acquire individual gun licenses. Although gun manufacturing remains legally permitted, the ban on purchasing firearms has rendered the trade unsustainable.

“The current policies allow manufacturing but ban purchases. This leaves us helpless,” laments Ahmad.

Skill and Legacy

Despite its challenges, the artistry of Kashmiri gunsmiths has been widely acknowledged. Walter Lawrence, the author of The Valley of Kashmir, praised their craftsmanship, noting: ”The well-known gunsmiths can turn out good guns and rifles, replacing parts so skillfully that it is difficult to distinguish between Kashmiri and English workmanship.”

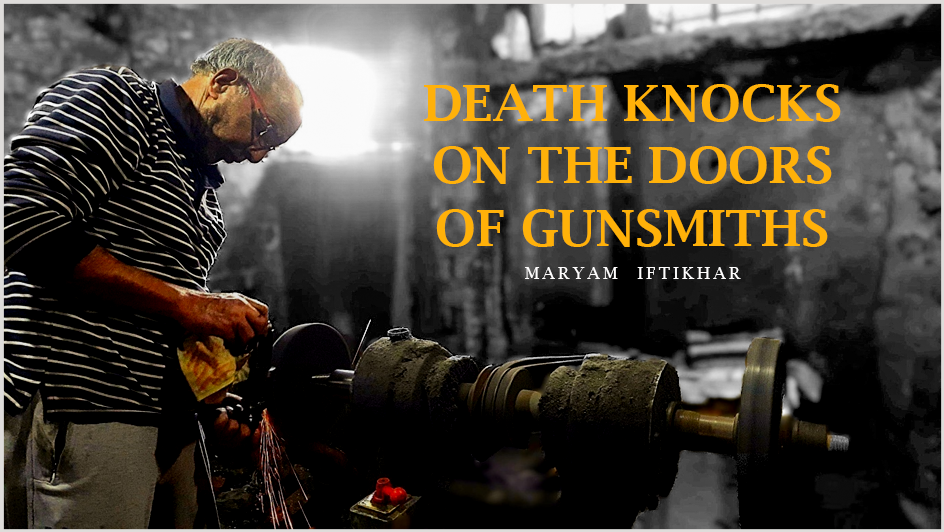

The craft’s survival owes much to artisans who repair and enhance guns with intricate hand-carved walnut gun butts, a signature feature of Kashmiri gun-making.

Government Initiatives

In 2023, the PM Vishwakarma Yojana was launched to support traditional craftsmen, including gunsmiths. The scheme provides:

- Armourer certifications.

- Toolkits worth ₹15,000.

- Loans of up to ₹3,00,000 with a 5% interest rate.

- Training programs, including a six-day drill and an advanced 15-day course, during which artisans receive ₹500 daily.

However, local gunsmiths argue that these measures are insufficient without the issuance of individual gun licenses. “In the entire Kashmir Valley, only nine gunsmiths remain. Youngsters avoid this profession as it doesn’t offer financial stability. Without serious administrative steps, this industry will vanish,” warns Ahmad.

A Fading Tradition

The once-thriving factories, bustling with activity, now lie silent and outdated. Despite holding industrial registrations, these facilities were never converted into industrial estates. Artisans like Javid Ahmad Ahangar continue working on single-barrel guns, but with minimal hope for revival.

Showkat Ahmad, who left the trade to repair electrical equipment, expresses his grief:

”For generations, my family made guns. Out of 15 factories, only two remain. I had to leave the trade to support my family, but gun-making runs in my blood.”

Zareef Ahmad Zareef, a Kashmiri poet and historian, echoes these sentiments: ”The uncertain situation in Kashmir has led to scrutiny and harassment of gunsmiths. The violence has caused the decline of many traditional vocations, including this one.”